The Wood Pellet Association of Canada (WPAC) recently partnered with the Arctic Energy Alliance (AEA) to produce 2025 Northwest Territories Biomass Week, a five-day event designed to help pellet producers, equipment manufacturers, installers, regulators, researchers, academia, governments and others to learn more about how biomass is transforming the way we think about energy, especially in Canada’s North.

More than 300 attendees participated in sessions that included the advantages of biomass, case studies, district heating, biomass supporting forest health, combined heat & power (CHP), bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), and biomass innovation.

The Northwest Territories is not part of North America’s electricity grid. Instead, this vast area operates on a remote electrical system using diesel fuel, hydro resources and natural gas. There is rising interest within the Northwest Territories to adopt biomass CHP, especially in remote communities, to get away from the high cost and GHG emissions associated with diesel. Also known as cogeneration, biomass CHP is the simultaneous generation of useful heat and electricity from a single plant using wood chips or pellets as the fuel source. Despite its promise, CHP has yet to make a meaningful impact in the Northwest Territories.

Broadly speaking, there are two categories of biomass CHP: combustion-based systems and gasification systems.

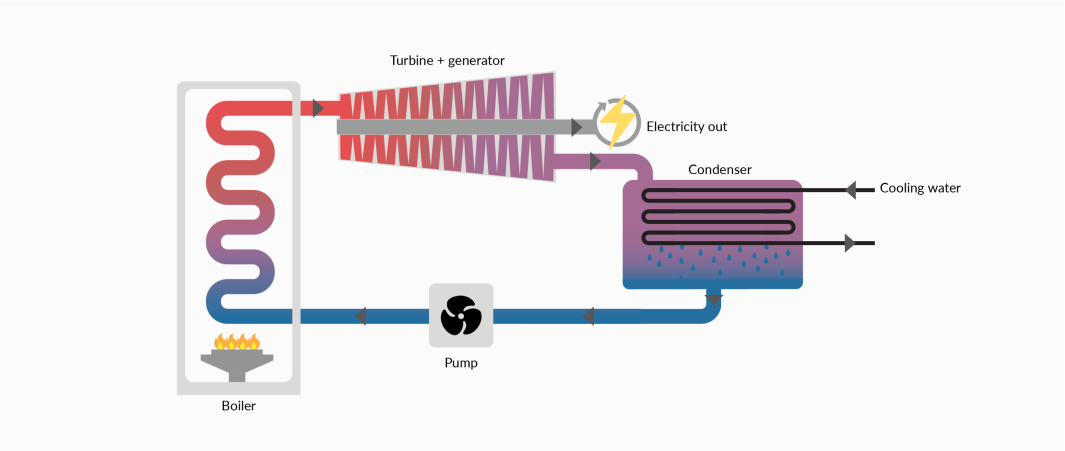

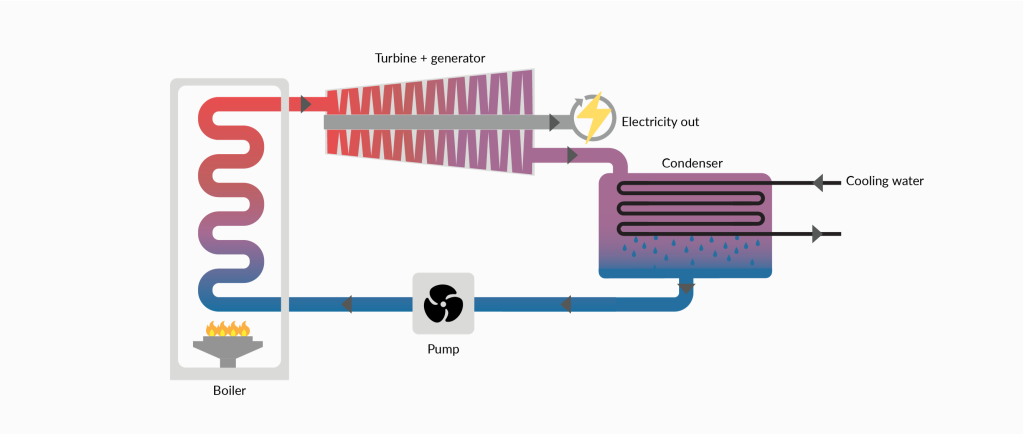

In combustion-based CHP—which is most common—electricity is typically generated by a steam turbine that uses a Rankine cycle. Biomass combustion heats water within a boiler to create steam. Steam pressure causes a turbine to rotate, spinning a generator where electromagnets move past conductors mounted in a stator, causing electricity to flow. Steam leaves the turbine and becomes cooled to a liquid state in the condenser. The liquid is pressurized by a pump and goes back to the boiler. High-quality exhaust heat is captured in a heat recovery device, and the heat energy is distributed, typically by hot water, to a district energy system or into individual large buildings.

Combustion-based CHP can also be operated using an Organic Rankine cycle (ORC). An ORC uses thermal oil rather than water as the operating medium. It operates at a lower temperature and pressure. The oil makes it easier to operate than a steam-based system in cold climates.

Combustion heats pressurized oil to 300°C, which expands to produce oil vapour to drive the turbine. ORC has an electrical efficiency of around three percent higher than a steam turbine and typically operates with a 5:1 ratio of heat to electricity generation.

With gasification-based CHP—a less common system—a process of gasification produces a synthetic gas that is used to fuel an internal combustion engine connected to a generator. Gasification is achieved through pyrolysis by partial oxidation of biomass using only about one-third of the air generally required for full combustion. The pyrolysis gas must then be treated to remove undesirable compounds, creating syngas, mainly carbon oxide, hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Syngas fuels an internal combustion engine that rotates a generator to generate electricity and heat.

While biomass CHP systems are common in many parts of the world, they have yet to be successfully deployed in the Northwest Territories. One significant barrier is the high up-front capital costs, especially when compared to heat-only systems, meaning biomass CHP systems must be operated continuously at a very high rate of energy output to be economically viable. The economies of scale tend to be too large for small northern communities.

A second challenge for small northern communities is to be able to attract highly qualified operating personnel, especially stationary/steam engineers, who are necessary to operate and maintain biomass CHP systems.

Despite these challenges, biomass CHP should continue to be investigated for potential deployment in the Northwest Territories and other remote communities across Canada. Equipment manufacturers continue advancing the technology, making it more accessible and cost-effective. The potential cost and GHG savings compared to fossil fuels warrant further effort.

This is the first of three articles on WPAC’s presentations during the event. Other articles include one on on BECCS and a status update on pursuing a new Canadian Standards Association Standard on small solid biomass combustors.

Gordon Murray is the Executive Director of the Wood Pellet Association of Canada.